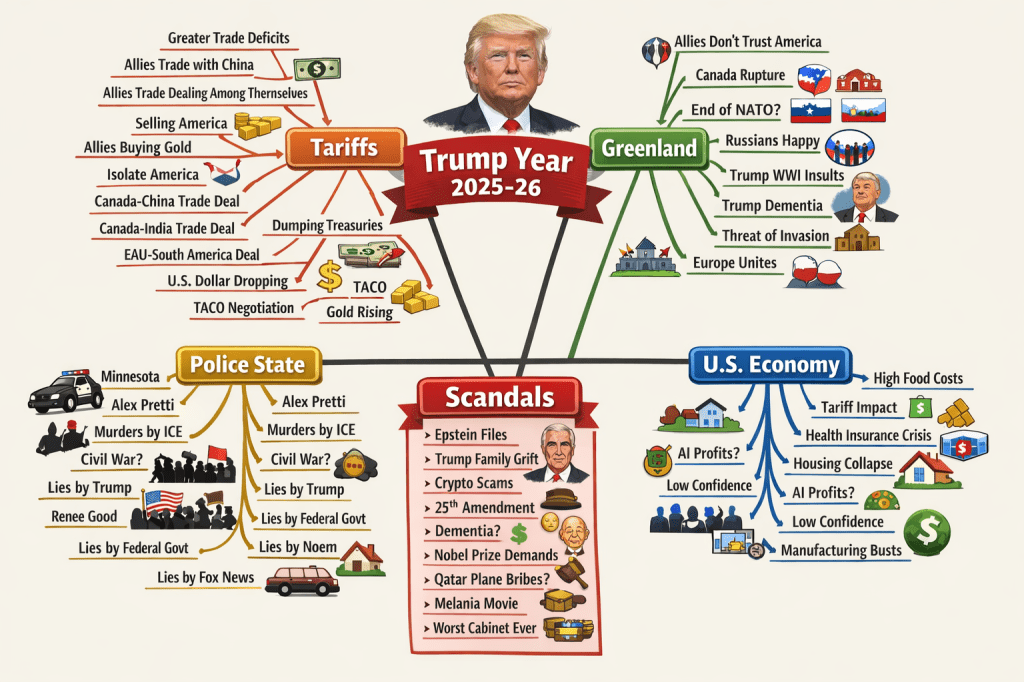

Good book for young men in their 20s and 30s. For this reader in his 70s, it provided some perspective on his life and a bit of a report card on how well he did. Scott Galloway is one of the nation’s top thought leaders. This book is a combination of an autobiography and his notes on how to conduct one’s life as a man. He cites the many issues of masculinity in today’s culture and society and offers his advice on relationships, education, career, family, work and health.

I think Scott has been very lucky. He had a loving and caring mother who filled the parenting roles when his father divorced her. I don’t think many men will identify with his life’s path. Scott worked very hard for his success but there were prices to pay in terms of his first marriage and health. Listed below are some notes of advice from Scott and my commentary regarding its validity and wisdom.

| Scott’s Notes | My Notes and Comments |

| Most boys come apart when a male role model leaves. If there is no father present, the son is more likely to be incarcerated than graduate from college. | I don’t think that I’m the exception. My father died when I was seven. I had a caring mother and family for help. I graduated from college. I dealt successfully with adversity. |

| Success comes when you put in small, consistent amounts of effort, every day and every week. | Success comes more from luck, connections and opportunity than effort. |

| College teaches you critical thinking-how to triage. | Depends on the classes, the teacher and the student’s desire to learn. Based on what I see, very few people have marshaled the knack of critical thinking, college or not. |

| The ratio of time you spend sweating to watching others sweating is forward looking indicator of your success. | Unless you are Donald Trump |

| Your body will sometimes make decisions for you when your brain won’t. Learn to listen to your body. | Good advice when you’re young, better and more valid advice as you get older! |

| Don’t be afraid to quit. Failing fast is better than failing over a long period. | As soon as you start a new job, develop a Plan B to escape if the job does not work out. Have an FU fund. |

| The best romantic partnerships are synced up on three things: passion, values and money. | Money or lack of it ruins many marriages and relationships. |