I’ve been an admirer of Andrew Ross Sorkin’s financial reporting for years, particularly through his work on CNBC, and I previously enjoyed his book Too Big to Fail, a definitive account of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. With that bias admitted upfront, I found 1929 to be an engaging and illuminating read. Though the book is lengthy—about 444 pages—it never feels like a dry history textbook. Instead, it flows with the narrative tension of a novel, making complex financial events accessible and compelling.

A background or interest in finance, economics, or banking certainly enriches the reading experience, but Sorkin’s storytelling makes the material approachable even for those who aren’t steeped in economic jargon.

A Rich, Relevant History

What makes this book especially resonant is how closely the late 1920s echo aspects of our present moment. The U.S. had recently emerged from a pandemic; optimism about growth and technological change was widespread; and the stock market appeared unstoppable. Investors—large and small—took on unprecedented leverage, borrowing heavily to chase rising share prices.

But economic momentum is fragile. Once confidence cracked, the market’s collapse was swift and devastating. The crash wiped out fortunes, triggered a steep economic downturn, and led to widespread unemployment. The government and the Federal Reserve lacked a clear or unified strategy, and their responses were often reactive, hesitant, or contradictory.

Sorkin offers a nuanced view of Herbert Hoover, depicting him not as the caricature of incompetence found in some earlier accounts, but as a leader who recognized the depth of the crisis and attempted—albeit imperfectly—to stem the damage. It’s a more sympathetic portrait than many readers might expect.

Vivid Personalities and Power Players

The book is populated with fascinating figures from finance, government and politics, including:

- Charles Mitchell, chairman and CEO of National City Bank (a central figure in the era’s excessive speculation)

- Winston Churchill

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- Senator Carter Glass

- Evangeline Adams

- Herbert Hoover

- Ferdinand Pecora

- and many others

Sorkin demonstrates how the interplay of personalities, policies, and economic forces created the conditions for both the boom and the crash. His research is broad, and his interpretations are measured yet insightful.

Reflections on Today’s Economy

Reading about 1929 inevitably led me to think about the state of the economy today. Although history doesn’t repeat itself exactly, the parallels are difficult to ignore.

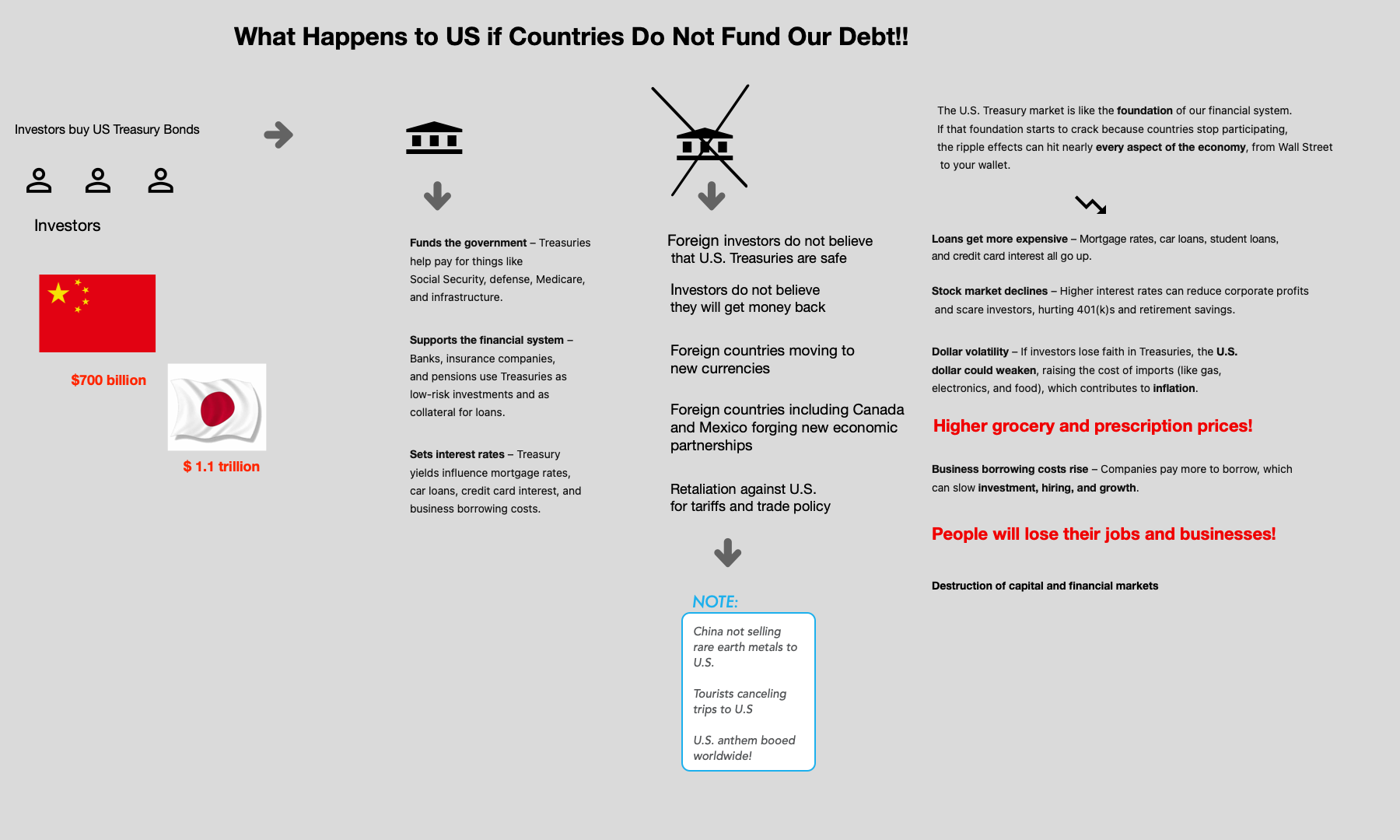

- Policy and leadership concerns: I have deep concerns about the current administration’s economic management. Policies such as tariffs continue to ripple through the U.S. and global economies, often harming consumers and industries rather than helping them.

- Social and economic inequities: Decisions to cut or withhold food aid and other social supports can create long-lasting harm. Tax structures continue to favor the wealthy, while those with the least must rely on charity to meet basic needs.

- Economic data skepticism: I find it increasingly hard to trust official numbers—whether on inflation, unemployment, or growth—given how politicized and selectively interpreted economic data has become.

- Uncertain impact of AI: Artificial intelligence is propping up portions of the stock market, but the long-term effects on employment, productivity, and corporate earnings remain unclear. Few leaders or analysts can articulate what the next decade will really look like if the hype fizzles.

- Declining trust in corporate leadership: Watching CEOs—particularly in tech and finance—publicly defer to political power has shaken my confidence in their judgment. Elon Musk is the most visible example, but he is not alone.

- The culture of greed: Increasingly, it feels as if greed has become our national creed. Even institutions that purport to offer moral guidance seem more interested in fundraising than fostering compassion or community.