Of all advice offered to seniors, none may be more foolish than “act your age.”

EAB 9/28/25

Month: September 2025

From Maginot to Meltdown: Watching the Guardrails Collapse

I once thought the Constitution, the rule of law, and basic common sense would protect this country from political chaos, the way the French believed the Maginot Line would shield them from invasion in 1940. The French were wrong—and so was I. What I did not anticipate was the near-total surrender of many corporate leaders to the political pressures of the Trump administration.

The word “hero” has been so cheapened in the past eight years that the bar hasn’t just been lowered—it’s been buried underground.

Before his death, I knew little about Charlie Kirk beyond a handful of YouTube clips where he “debated” college students. His philosophy struck me as shallow, reactionary, and hostile to nearly every step of progress made since the 1960s—civil rights, women’s rights, gay marriage. To me, he seemed like this generation’s David Duke.

As much as I would love to be a historian looking back at this moment from 20 or 30 years in the future, that’s exactly how much I despise living through the chaos in real time.

Strangely enough, comedians have become the most responsible and courageous voices in these perilous times, while many of our politicians and representatives play the role of clowns.

Now, with Jimmy Kimmel’s indefinite suspension, we’ll see whether the promised economic and cultural backlash against Disney, ABC, and their affiliates materializes. As for Kimmel himself, I would not be surprised if he decides not to return at all to his show.

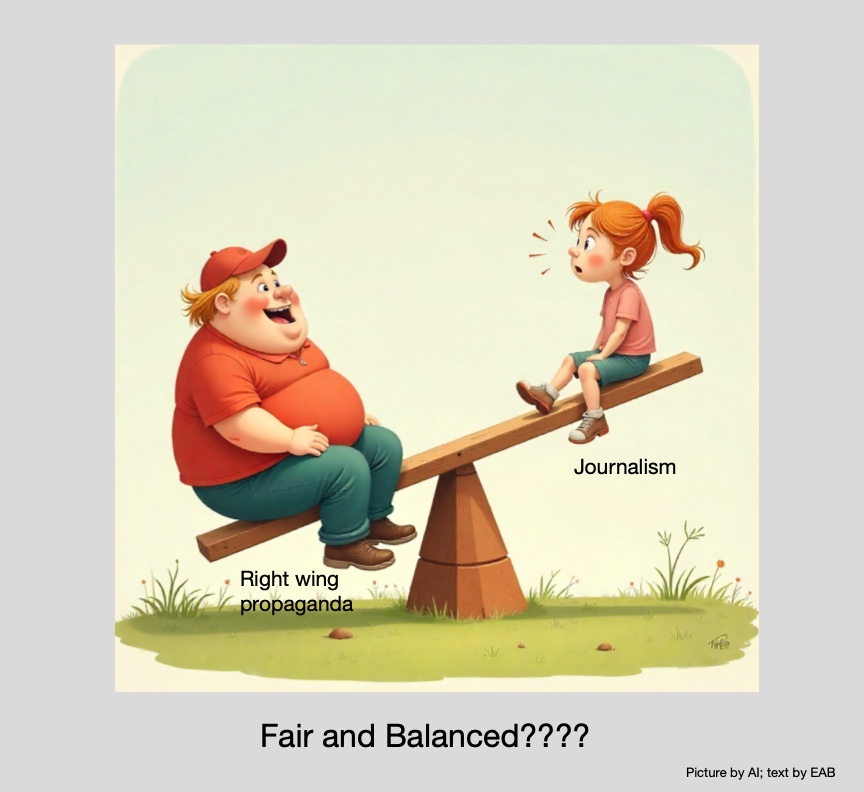

Fair and Balanced??

Fox News Channel host Brian Kilmeade apologized for advocating for the execution of mentally ill homeless people in a discussion on the network last week, saying his remark was “extremely callous.” (Still has his job)

MSNBC fired its senior political analyst Matthew Dowd after he suggested on air that the slain conservative activist Charlie Kirk’s own radical rhetoric may have contributed to the shooting that killed him.

Civil War??

I’d say this analysis from outside the United States and about the United States is dead on and reflects my thinking about the end of the American dream. I don’t think things will change, certainly not for the better. My sense is that there will be a “Civil War” in this country and it probably has already started.

The United States is a dangerously volatile country. There has always been a palpable element of derangement in its social order. It has a record of assassinations and attempted assassinations, and a perennial problem with violent crime which is matched by almost no other first world country. But what is happening now feels different: apocalyptic and inexorable. And the reason it cannot be stopped is that the people, both the population at large and those who are supposed to be in charge, do not want it to stop whatever they may claim.

If they sincerely wanted to put an end to it, they could do so in a moment of reasonable consensus. But they have consistently resisted any attempt to enforce standards or controls on the virulent social media activity which is undermining the real freedoms they revere. So the tide of what would once have been called “extremism” – the incitement of violence and the perpetration of blind hatred – are now the accepted currency of political discourse.

Janet Dailey The American Dream is ending in a Psychotic Breakdown The Telegraph

Book Review: King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution: A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation by Scott Anderson

After reading this book, it’s easy to understand why U.S. relations with Iran remain so strained and why so much hostility exists toward America. For nearly a century, presidential administrations have made diplomatic blunders, compounded by intelligence failures that shaped disastrous outcomes.

I recently finished Tim Weiner’s The Mission: The CIA in the 21st Century, which documented the CIA’s missteps in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and elsewhere. Anderson’s account shows the same pattern: Did we get anything right?

The intelligence failures in Iran were staggering. Agencies recorded Ayatollah Khomeini’s speeches but never bothered to translate them—missing clear warnings about his intentions. Meanwhile, the U.S. continued to prop up Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a weak and indecisive ruler despised by his own people. Ironically, his wife, Farah Pahlavi, displayed far more backbone and foresight. Yet to Washington, Iran’s real value was simply the oil beneath its soil.

Equally unconscionable was the way U.S. embassy staff in Tehran were treated as expendable pawns. The Carter administration fully understood the risks—especially after allowing the Shah into the United States—yet left personnel exposed to the fury of revolutionary crowds.

The lack of coordination between diplomatic and intelligence communities in the 1970s was nothing short of criminal. Mixed signals to the Shah, who desperately needed guidance and resolve, only deepened the chaos. Even today, the lingering question remains: Did Ronald Reagan deliberately delay the hostages’ release until after his inauguration?

Anderson does an excellent job highlighting both the heroes and villains of this tragic story. One memorable account involves teacher Michael Metrinko, who earned the respect of his Iranian students by deliberately standing up to—and physically subduing—the toughest among them.

By weaving personal tales with geopolitical history, Anderson makes the Iranian Revolution come alive in all its complexity. The result is a powerful and unsettling reminder of how deeply poor leadership and intelligence failures can alter history.

Book Review: Miracles and Wonder: The Historical Mystery of Jesus by Elaine Pagels

As an agnostic, I opened this book hoping it might shift my faith-doubt meter. It didn’t. Perhaps I expected too much.

Elaine Pagels, a distinguished scholar of religion, offers a deeply researched exploration of the history, culture, and legends surrounding Jesus. She examines familiar themes—the virgin birth, Jesus as prophet, miracles, crucifixion, and resurrection—while weaving in theories, conjectures, and historical possibilities. At times, though, her inquiry stops short of resolution, leaving questions dangling.

She does not shy away from provocative possibilities: Was Mary a prostitute? Was Jesus the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier? Was Jesus even buried after crucifixion, or left, like most executed criminals of the era, to scavenging animals?

Pagels acknowledges that the gospels themselves—written decades after Jesus’ death—are a blend of myth, storytelling, and propaganda designed to win followers. Yet she ends with a surprisingly devotional note: “The point is clear as a lightning flash; God can make a way out of no way.” She praises the gospels for offering what humanity craves most—an outburst of hope.

That left me puzzled. How much of Jesus’ life was historical, and how much was invention? If much of it was propaganda, why cling to its hope-filled message? For me, the book opened doors, raised intriguing questions, and stirred thought—but ultimately left me standing where I began.

To Lob or Not to Lob

There are five dreaded labels in the pickleball world that no one wants to wear: sandbagger, hooker (that’s a cheater on line calls, for the uninitiated), poacher, banger, and—my personal cross to bear—lobber.

Now, I can’t speak for the first four, but I’ve earned a reputation for being that last one. Yes, I lob. Sometimes more than once. Occasionally more than “socially acceptable.”

One of my partners recently suggested that I might want to cut back. Apparently, I’ve been annoying some of my fellow players. The eye rolls and glares haven’t escaped me, and I’ll admit I’ve even apologized a few times for exceeding the unofficial “lob quota.”

But here’s the thing: the lob is not the weak, outdated, sneaky shot it was once considered. Years ago, pros and commentators sneered at it. You almost never saw it on the big stage. Today? Pros lob often, and they lob well. It’s a legitimate strategy—a way to reset a point or outwit opponents who camp at the kitchen line like they’ve paid rent there.

At 73, I don’t have the hand speed or footwork of a 30-year-old tournament player. Just as a pitcher with a fading fastball learns to mix in more curveballs and off-speed junk, I mix in more lobs. For me, it’s both a survival tool and an offensive weapon.

If I lob you, take it as a compliment: it means I think you’re good enough to deserve it.

That said, I try to be mindful. I don’t lob against beginners, players with mobility challenges, or anyone who tells me they just don’t want to chase them down. I do not use the sun as my secret doubles partner, I do my best not to lob into it deliberately. (Though, if I see a wide-open chance for a clean winner? Sorry, I’m taking it. I’m not that saintly.)

At this point in my pickleball journey, I want opponents to bring their best game against me—lobs, drop shots, body-bag drives, all of it. It’s part of what makes pickleball fun and unpredictable. And when the day comes that I can no longer compete, I’ll gladly hang up my paddle and write about pickleball instead of playing it. Or maybe I’ll take up chess—where, mercifully, no one will complain about a well-timed lob